Working Memory: Don't Lose It, Use It

Kids need the brain space to play with new concepts in order to learn them.

Posted March 17, 2024

KEY POINTS

Working memory is the gatekeeper to all new learning and is housed in the prefrontal cortex.

The capacity of working memory storage is limited to just three to five items at a time.

When new concepts are relevant to kids' lives, they are more likely to practice and build on them.

Put away your phone, picture this, and remember it. The entry to all new learning is like a doorway. Information crosses the threshold ushered by what captures our attention. Our capacities to see, listen, smell, and feel invite new ideas through the entrance into a room where we can play with them and make sense of them. This is the wondrous play space of working memory.

Working memory is the ability we have to play with new ideas before we commit them to something memorized, learned, or embedded in our brains. Housed in the prefrontal cortex, working memory relies on a set of circuits that allow us to hold information without fully processing it, before we make meaning. This play space, mind you, can only accommodate a few meaningful items at a time, three to five to be more precise. Working memory is a fabulous but highly constrained resource. It is the gatekeeper to learning, but it is small and vulnerable.

Making Meaning

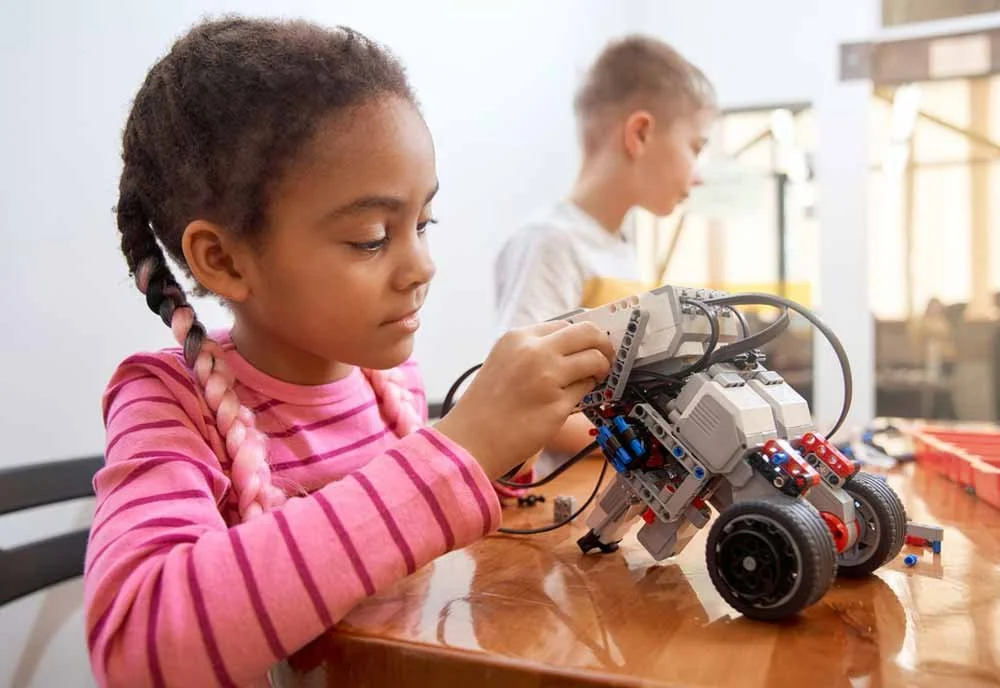

Much of the new information being processed as part of working memory will not be remembered unless it is salient to us, unless we practice and repeat it until it becomes knowledge. It could be learning to ride a bike to keep up with a big sister or understanding programming and electronics to build a radio or robot.

One miracle of our learning apparatus is that it is designed to achieve very different short and long-term learning goals. But they all begin the same way—with exposure to new learning using our working memory.

Think of what a beautiful and effortless thing it can be when we become fluent in something—reading, playing a favorite instrument or sport, speaking a new language. Fluency and mastery are when skills and information become so internalized, they feel almost automatic and easy to do. Not only are they embedded they are permanent, stored in long-term memory. They are like a savings account to be drawn upon as needed and built upon as a foundation.

Use It or Lose It

When students have had effective learning experiences then get tested, the information they need is available to them. It can’t get “lost." However, information that is new, that is part of our working memory, can be elusive. Anyone taught new things who has not had the chance to work with the material, to give it meaning and relevance, practice it, build things with it, can “lose” it. Why? Because it hasn’t become embedded in long term memory as prior knowledge.

Divided Attention

Absence from school, distractions of daily life, attention splintered and divided from scrolling and switching between applications on a cellphone—all of this can affect the stability of prior knowledge. Today we have all three in spades and the impact on learning is real.

As we lament declining, disappointing and even dismal student performance across the globe, consider what distraction does to working memory and information storage. Since 2010, the attention people pay to screens has risen astronomically. Young people are using them day and night, inside of school and out. And as they scroll and split-screen, attracted for a moment here and a moment there by what is new, strange, provocative, funny, action-packed or beautiful, the doorway to working memory gets blocked.

That’s the amygdala, the emotion center of the brain, overriding the capacities of the prefrontal cortex to control focus and attention. Shiny objects, TikTok dances, highlight reels, all can draw our attention. Messages that engage our emotions in happy and horrible ways can quite literally squander the limited capacities of our working memory. Think about this as you imagine the number of times our kids “check their phones” and see something that upsets them. These activities literally block the entrance to new learning.

In those moments when we “have to check" our phones, these devices are inducing states of distraction, interrupting the operation of our working memory. If we see something that is upsetting, the distraction is even worse and may go on for a long time. Instead of building and strengthening working memory like a muscle, we are weakening and wasting it.

You don’t have to be a scientist to see the consequences. They are all around us and are a catastrophe for learning. The less information you introduce through the gateway at the front end (new learning), the less you are going to have to play with and build on to bolster prior knowledge and achieve fluency or mastery.

And for students whose learning experiences to date haven’t established foundational knowledge, distractions hold particularly disastrous consequences.

The Future of Learning

The roadmap for the future of learning and our learners is clear and urgent. We have an opportunity to use what we know about the brain to strengthen, not weaken the learning apparatus of every young person.

The digital world can and will be an enormous resource to learners but much of the time, that is not what it is being used for. Today, digital life has become a habit through which many of us gut-check our worth, drive our own distraction, interrupt our focus, and reduce the most important resource we have—our ability to learn from and with others.

Read the article on Psychology Today.